A pretty little strawberry patch flourishes in the backyard of our magazine. Normally, our staffers compete with the birds in June for ripe berries but this year most of us are avoiding the patch because someone saw a family of snakes living in the dense foliage.

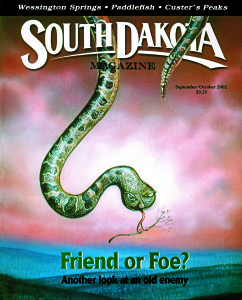

I don’t mind the backyard snakes but I know ophiophobia, extreme fear of snakes, is prolific. In 2002 we published a story on rattlesnakes and asked Madison artist John Green to paint the cover — a friendly rattler holding an olive branch in his fangs. We were met with the biggest reader backlash in the history of the South Dakota Magazine. Readers wrote scathing letters and threatened to cancel their subscriptions if we ever put a snake on the cover again.

We joked that the incident taught us why most magazines put pretty girls and fattening foods on their covers. But we never did it again.

Not all people run at the sight of snakes. A.M. Jackley was considered a hero when he became the state’s official rattlesnake hunter (a paid position) in 1937. He hunted them to help neighbors at first, and discovered he had a talent. Jackley had some opposition from early animal rights believers, but scoffed at his naysayers. “Those of us who have looked upon the still form of a child lying on the prairie with a rattlesnake coiled beside it, or have seen one bitten and suffer death, cannot take kindly this opposition,” he argued.

Ben Smith of Fort Pierre is South Dakota’s modern-day unofficial rattlesnake catcher. Smith grew up on a farm south of Fort Pierre and watched his dad kill snakes and save the rattles. When he was old enough, he started saving the rattles. He eventually began hunting them himself. People know they can call Smith with a snake emergency. “It’s an adrenaline rush to be out there,” he told us. “I’ll come and if I find them I’ll take them out.”

Earl Brockelsby, the father of Reptile Gardens near Rapid City, also felt that rush. But he didn’t kill snakes; he played with them. He first began to work with reptiles as a young guide at a roadside attraction near the Badlands. He soon learned he had a rapport with them. “Every time I came near their cage, they would coil up into a striking position with the neck in an ‘S’ … and rattle vigorously,” Brockelsby wrote years later. “Still, when I reached into the box to lift one out, it wouldn’t strike and would quit rattling once it was in my hand. Then it would crawl up my shirt sleeve, out the collar at my neck, then over my ear, and force his way under my hat where it would then coil tightly on top of my head.”

Brockelsby shocked and impressed the tourists with such tricks as the summer progressed. The tips he earned that summer were a snake talent, and that eventually led to Reptile Gardens. A new book by Sam Hurst, Rattlesnake Under His Hat, tells of Brockelsby’s adventures.

All we have here in our Yankton strawberry patch are harmless garter snakes, and yet I don’t think we have a single magazine staffer who would let one crawl up his or her shirt. Anybody want some pick-your-own strawberries?